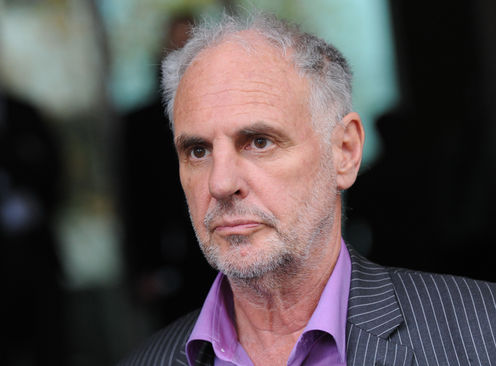

People who operate on the edge risk falling over it and into the abyss. And euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke has been in freefall since it emerged he had email contact with a healthy 45-year-old West Australian man who took his own life in May.

Nigel Brayley, who did not have a terminal illness, joined Nitschke’s euthanasia advocacy group Exit International in February. He then bought its “how-to” guide on suicide (The Peaceful Pill Handbook), and illegally procured its drug of choice Nembutal.

Brayley made his lethal intentions clear, but Nitschke deemed him rational and not in need of psychiatric help.

In a blistering rebuke, beyondblue chairman Jeff Kennett accused Nitschke of failing in his duty of care and sending the voluntary euthanasia movement back to the dark ages. Kennett is right.

A duty of care

Nitschke owed Brayley a duty of care. He engaged with Brayley as a medical practitioner and was aware he had suicidal plans, a cardinal symptom of depression. Duty of care means acting in the patient’s best interests at all times.

Nitschke can appeal to best interests when helping terminally ill people end their lives. These folk suffer intolerably, or will do courtesy of cancer, motor neurone disease, or some other unutterable scourge.

Death can be in someone’s best interests when their disease is fatal and degrades well-being to the point of despair.

Enter Brayley. No known illness, but a cascade of events that made him a prime candidate to feel bad, and get depressed. In 2005, his live-in girlfriend went missing and was never found.

More recently, he was investigated for the 2011 death of wife Lina Brayley, whose body was discovered at the foot of a cliff. And then Brayley lost his job in the oil and gas industry.

Nitschke asserts that:

In retrospect, it looks as though he was fearful of a long period of incarceration. A person that’s confronting that sort of dire circumstance can…make a clear rational decision that death might be the preferred option.

The doctor gravely misinterprets how life events figure in depressive decision making.

The trouble with depression

Stresses such as job loss, money trouble, relationship breakdown, and indeed criminal investigation figure in two-thirds of depressive episodes.

On one hand, it can seem “rational” that people staring down adversity are miserable; depression, like other negative emotions, signals that things haven’t gone your way. But depression differs from ordinary reactive sadness.

Unrealistic pessimism taints nearly every prediction. Depressed people place higher likelihood on random accidents or illness befalling them; fates they can’t possibly divine.

Any person acting against their apparent best interests needs their decision-making capacity scrutinised. This formal assessment is made by a trained practitioner in line with a legal benchmark.

It tests that person’s ability to understand and weigh information pertinent to a decision. Depression works against this capacity because you almost always give undue weight to bad outcomes.

Nitschke claimed on ABC’s 7.30 that:

If a person is so depressed that they have lost capacity, then they can’t articulate anything…the fact he was so insightful in his decision…indicates to me that he was indeed a person who had not lost capacity.

This is misguided. People with depression can meticulously plan their deaths, and eloquently describe a joyless future. In short, the rational failure of depression can be fully fluent.

Invoking the slippery slope

Nitschke has countered that:

They [the medical profession] simply can’t get over the idea that sometimes suicide has got nothing to do with depression and nothing to do with medicine.

But, as psychiatrist Chris Ryan has commented, it would be an unprecedented feat if Nitschke could rule out depression by email.

Nitschke has also pointed out that he was not Brayley’s doctor. But doctors can’t take off their medical hats at will.

At least one legal case suggests being aware of an emergency and able to intervene means Nitschke can’t suddenly choose to be an ordinary citizen.

People with lives made intolerable by illness can autonomously prefer a quick painless death to even the best life offered by palliative care. But Nitschke’s action fuels those saying euthanasia is a slippery slope to unjustified medically assisted death.

French writer and philosopher Albert Camus thought the absurdity of life made suicide a rational option. Camus may well be right, but when existential angst pushes us to the brink, doctors shouldn’t be the ones tipping us over.

Exit International must re-think its mission or risk losing the precarious public sympathy for its cause.

If you have depression or feel very low, please seek support immediately. For support in a crisis, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14. For information about depression and suicide prevention, visit beyondblue, Sane or The Samaritans.

Paul Biegler has received funding from the Australian Research Council. He is a former emergency physician and the author of The Ethical Treatment of Depression: Autonomy through Psychotherapy (MIT Press 2011) which won the Australian Museum Eureka Prize for Research in Ethics.