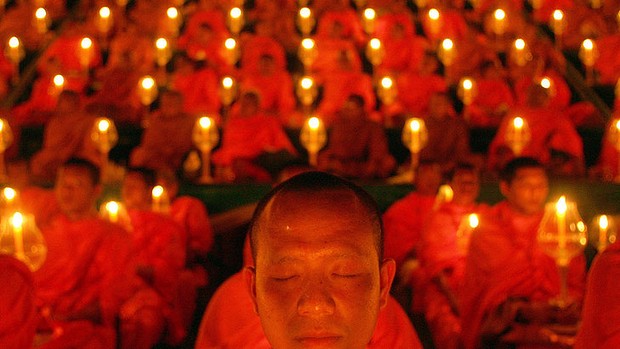

Some believe that worshippers respond to brain activity that enables heightened feelings of connectedness with things. Photo: Reuters

When neuroscientist Andrew Newberg scanned the brain of ”Kevin”, a staunch atheist, while he was meditating, he made a fascinating discovery. ”Compared with the Buddhist monks and Franciscan nuns, whose brains I’d also scanned, Kevin’s brain operated in a significantly different way,” he says.

”He had far more activity in the prefrontal cortex, the area that controls emotional feelings and mediates attention. Kevin’s brain appeared to be functioning in a highly analytical way, even when he was in a resting state.”

Would Newberg find something similar if he scanned my brain? I, too, am an atheist. This is largely the result of my upbringing (my father is a theoretical physicist, who, as a former director-general of Cern, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, set up the Large Hadron Collider that is searching for the Higgs boson, or so-called ”God” particle – though many physicists loathe that phrase), but also of prolonged investigations into other religions to see if I was ”missing” something central to billions of people worldwide.

Neuro-scientist Michael Persinger tried to simulate these feelings with his God helmet in the 1990s.

In this spirit, several years ago, I attended an ”Alpha” course, a 10-week introduction to evangelical Christianity. It utterly failed to convince me but, during a service, another ”recruit”, Mark, fell to his knees, babbling ”in tongues”.