On Tuesday night, the Abbott government will announce that the free visit to the doctor for most people is to become a historical artefact of Australian life.

It will be one of the most controversial decisions that the government will take.

It will also be one of the hardest-fought as Labor and the Greens try to block it in the Senate. Clive Palmer’s party will get to sit in judgment.

Today, four out of five visits to the doctor are free to the patient because the doctor “bulk bills” the charge to Medicare.

But this proportion is expected to fall to just a tiny proportion when the government announces that patients will start paying a fee of about $7 for each visit to a GP.

In the jargon, this is called a co-payment. In Labor’s lexicon, it’s a GP tax.

One unhelpful consequence for the health system might be a rush from GP clinics to free public hospital emergency rooms as patients avoid the new fee.

This could lead to insupportable burdens on a creaking hospital system. The government solution? It will empower the states to impose a fee on emergency rooms too.

The new fee will apply from July 1 next year. That gives the system time to prepare; it gives the government more than a year to make the case for it; it gives the opposition more than a year to run a scare campaign against it.

Why change a settled fact of daily life? The basic argument is that a free commodity is an abused commodity.

As Joe Hockey put it last week, “there is no such thing as a free visit to a doctor”.

“Government services are somehow deemed to be magically free but of course they’re not free, they are paid for by the taxpayer.”

The government argues that by making the patient feel a part of the cost directly, it can curb demand for unnecessary GP visits.

It will make Medicare more sustainable, argues the minister for health, Peter Dutton.

“In our country with a population of 23 million people, the taxpayer currently funds 263 million free services a year under Medicare and, if we are to have a strong and sustainable health system in to the future, that figure is not sustainable,” Dutton said in a speech.

“While all components of federal health spending have risen greatly in the past 10 years, the fastest growing element has been Medicare payments,” the minister wrote last month.

“Last financial year the Commonwealth spent $18.6 billion on Medicare payments, an increase of 5.3 per cent from the previous year although the population only grew by an estimated 2.6 per cent.”

New demands on the health budget loom, some daunting. Three are cited commonly by health policy experts: rapid increases in “lifestyle diseases” such as diabetes; a big rise in dementia and brain illnesses as the population ages; increasing demand for expensive interventions with the advent of new medical technologies and cheap genome-mapping.

Doing nothing in the face of all this, says Dutton, is not an option.

But don’t we already pay for Medicare through the 1.5 per cent Medicare levy, which is soon to rise to 2 per cent to help pay for the national disability insurance scheme?

The 1.5 per cent levy only covers a fraction. If it were to cover all federal health spending, it would have to rise to 9.5 per cent, according to the government.

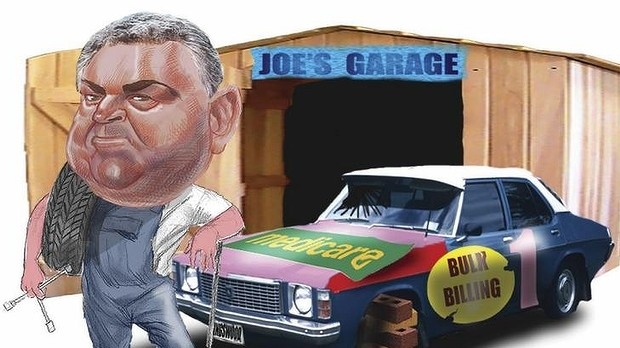

Dutton has likened Medicare to a Kingswood, a 1980s model in need of remodelling.

“When it was conceived decades ago you could buy a house in our cities for between forty and eighty thousand dollars, the Holden Kingswood was probably the best-selling car.

“It was a different world. Much has changed. I doubt many Australians would find the features of a 1970s or 80s Kingswood would meet their expectations of a vehicle today.”

As Holden prepares to go out of business, the government wants to say good bye to its analogous medical model, the Medicare Kingswood.

But the attraction of the Kingswood is that, while it may be outmoded, it’s certainly affordable.

What happens to people living in poverty? To the chronically ill poor who need to see a GP often but can’t afford it?

Labor will home in on this point. Bill Shorten has described the government’s much-speculated plan for a co-payment as “the end of universal health care in Australia.”

Shorten said this week: “We believe that the quality of health care you get in Australia should depend upon your Medicare card not your credit card. We do not support a new GP tax.”

Dutton’s plan has two safeguards. One, GPs will have the discretion to continue with bulk billing and to waive the $7 charge in cases of hardship.

Two, there is to be a so-called “safety net” where patients will not have to pay the fee after about 10 or so visits in any one year.

The idea of imposing a fee for GP visits is not new. One awkward fact for Shorten is that Labor actually introduced one in 1991.

Facing a looming rise in health spending, the Hawke government introduced a $3.50 fee. In fact, today’s proposal for a $7 fee is pretty much the Hawke co-payment, updated for inflation.

New Zealanders pay a $17 GP fee. The Abbott government’s commission of Audit proposed a $15 fee for Australians.

But the government’s starting point was a paper written by a health adviser to Abbott when he was health minister, Terry Barnes. He wrote a recent paper proposing a $6 co-payment.

“I didn’t pluck that number out of thin air,” says Barnes, a former senior public servant and now a consultant at Cormorant Policy Advice. “I took the Hawke government’s $3.50 and adjusted it using the Reserve Bank’s deflators,” which gives you $6.25. Dutton then bulked it up a little to around $7.

“It’s hard for Labor to oppose this,” says Barnes, “because it’s basically the Hawke proposal.” That will not stop Shorten for a moment.

Working from the Tony Abbott handbook for successful opposition leaders, Shorten will put opportunism ahead of consistency. Did Abbott care that John Howard had proposed carbon emissions trading scheme?

Shorten will seize on the GP fee as a broken promise by a government that promised no new or increased taxes.

He will demonise it as the end of the Australian fair go and the Americanisation of Australian life.

What happened to Hawke’s $3.50 fee? It was abolished after just three months by the new Labor leader, Paul Keating.

The Dutton argument, however, is that he’s not ditching Medicare but strengthening it.

He is not introducing any of the other dramatic ideas from the Commission of Audit. Medicare is not to be means-tested, for instance.

Terry Barnes says that “as long as you keep the basic fabric of Medicare intact and keep changes on the margin, you’re not Americanising the system. That includes keeping timely and affordable access to world-class health care – it doesn’t imply totally free access.”

If the government gets its way, what will happen to the number of visits to the doctor?

The Treasury estimates that the total number of GP visits, now around 120 million a year, would fall by about only 1 per cent. This seems implausibly small.

The Treasury estimate is really no better than a guess. The president of the Australian Medical Association, Steve Hambleton, thinks it’s plausible, nonetheless.

“I think in reality you’d see a surge in the number of visits in the months before it was introduced, you’d see it die off, maybe halve, in the month it’s introduced, then it’d pick up and adjust. Health isn’t a discretionary service – you can’t plan when the kids will be sick.”

But if the Treasury and Hambleton are right, and there is scant change in the number of GP visits with a fee of about $7, then why bother at all?

There are several arguments. One is that it will improve the quality of GP visits.

The average GP visit is just six minutes. Under bulk billing, there’s a commercial incentive for doctors to churn through as many patients as possible.

Medicare pays the doctor a flat $36 fee for a standard consultation whether it takes 15 minutes or 15 seconds. Say Barnes: “Doctor behaviour might change too if they’re not providing a free service. Maybe they won’t be so focused on six-minute medicine…getting patients in and out, writing referrals and scrips” as fast as possible.

Another argument involves the payment itself. Where does the copayment of around $7 go? Under Peter Dutton’s plan, the Medicare rebate paid to the GP would fall by some $5 to offset the new copayment. So that would be a saving to the federal budget of some $600-700 million a year.

But the GP would get to keep the other $2. This is partly designed to win over GP support for the change; it’s also the government’s hope and expectation that, with more money for GPs, they will use some of it towards the really big area of potential gain, managing chronic diseases more actively.

We know that Labor and the Greens are primed to block the GP fee. What about the Australian people? A Nielsen poll commissioned by Fairfax in March tested support for a $6 copayment. It found opinion divided right down the middle – 49 per cent for and 49 per cent against.

This was pretty remarkable. The government hadn’t even started to make the case for the fee. It suggests that Hockey’s overarching theme of an “end to the age of entitlement” has real resonance with half the country, at least.

But it will be a real struggle. The AMA’s Hambleton tells of a GP friend who’d raised the idea of a GP fee with a couple of older people, people he considered friends. “They told him, ‘if we have to pay $2 to see a doctor, we’d rather die’.”

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald